Menu

Adrienne von Speyr

Adrienne von Speyr was called to live the life of heaven on earth. Even her work as a doctor flowed from loving obedience to this call. Hers was a life in the world of prayer: the life of the Trinity opened to men, the life whose light reveals to us the true nature and purpose of creation.

The Early Years

Adrienne von Speyr (1902-1967) was the second of four children born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, to Theodor von Speyr and his wife Laure, née Girard, who had married just a few years before Adrienne’s birth. Theodor, an opthamologist, came from an old Basle family that was already known before the Reformation for their work as bell-makers, sacred artists, and printers; even today, some of the famous “Cloches de Bâle” (Clocks of Basle) still bear the name of the Von Speyr workshop. Later, the family produced doctors, pastors, and successful businessmen. Adrienne’s mother, for her part, came from a family of watchmakers and jewelers who had flourished in Geneva and Neuchâtel. Place matters: Adrienne would always retain a vivid memory of the austere beauty of her native Canton, the Jura, and would often revisit it in thought during the last years of her life.

- Family photo with Adrienne in her mother’s arms

- Adrienne as a little girl

- Les Tilleuls, the house of Adrienne’s grandmother, which was a refuge for her as a child

Despite her frequent bouts of ill health, Adrienne was a quiet, temperamentally cheerful child. From her earliest years, she had a lively interest in religious matters and was precociously critical of the narrow Protestant confessionalism in which she had been raised. She felt especially at home in her grandmother’s country house, “Les Tilleuls.” Adrienne would never grow tired of recalling this extraordinarily good woman who had shown her such warmth and understanding.

During the holidays, Adrienne and her siblings were allowed to visit their uncle, Dr. Wilhelm von Speyr, who directed the Berne Canton’s public mental hospital, called the Waldau. Even as a child, Adrienne showed no fear of the inmates, but seemed to possess a mysterious gift for understanding, communicating with, and calming them. Recognizing this gift, her uncle did not hesitate to send her, doll in hand, to the most afflicted patients. The inner and outer landscape of the Waldau became a kind of home away from home for Adrienne.

High School and Illness

Another unforgettable experience for Adrienne was her time as a high school student in La Chaux-de-Fonds, where, in addition to learning Latin and Greek, she acquired a mastery of French, a process she would later effortlessly repeat with German. She loved succinct, precise speech and had a positive aversion to every form of chatter. The only girl in her year, she managed her status as top student in a light, playful manner. Her effervescent temperament, her unfailing cheerfulness, and her loving humor made her the idol of her class.

Adrienne was not yet fifteen when she lost her father. As he was preparing to move his practice to Basle, Theodor suddenly fell ill and died a few days later. Adrienne, who outshone her school-fellows in both talent and maturity, felt duty-bound to take on a great deal of extra responsibility at home. The resulting heavy burden led to a physical breakdown and a life-threatening case of tuberculosis. After a summer in the sanatorium at Langenbruck, she spent almost two years at another sanatorium, this time in Leysin; here she passed long hours in prayer and became acquainted with the world of suffering. Only half-recovered herself, she took to visiting other houses in order to assist the dying.

- Adrienne kneeling in front of a group of patients and nurses at the sanatorium of Langenbruck, Switzerland (1918)

- Adrienne as a high school student in La Chaux-de-Fonds (ca. 1917)

Wrestling more intensely than ever before with the question of the true Church, she often found herself praying in the Catholic chapel. Discharged from Leysin, but still not completely well, she enrolled in a nursing course in St-Loup. She suffered a relapse and was sent to her uncle in the Waldau for treatment. Here, at last, she was restored to health.

Adrienne was now nineteen. She enrolled in a girl’s high school in Basle, where her family had recently taken up residence. She learned German, and, after only a year and a half, was able to pass her graduating exam (the Swiss “Matura”) in that language. Here, too, Adrienne very quickly became the moral center and spokesman of her class, and she was taken into the confidence of the school director and her fellow students alike. When Adrienne’s mother tried to arrange her marriage with a bank clerk, she declared her desire to study medicine instead–for which her mother refused any financial help. Even her uncle in Berne energetically opposed her plans. Thus began a long, extremely difficult period in Adrienne’s life, in which she was forced to pay her own way through medical school–as if that were not already demanding enough–by tutoring in her spare time.

What especially kept her going was her passionate concern for her suffering fellow human beings. She was entirely in her element in the clinical semesters, and she very quickly obtained permission to take frequent night shifts in intensive care. She loved to recall those nocturnal hours when she would quietly go from bed to bed in order to calm the suffering, pray with the sick, and prepare them for death. Her teachers were astounded by her intuitive gift for difficult diagnoses. Among them was the surgeon Gerhard Hotz, whom she devotedly admired and whose early death affected her greatly. It was at medical school that she also established life-long friendships with her fellow students Franz Merke and Adolf Portmann, who would later become professors in their own right.

Marriage and Professional Life

While vacationing in San Bernardino, Italy, in 1927–it was the first time she was able to afford holidays on her own–Adrienne was introduced to the Basle historian Emil Dürr. Thanks in large part to the matchmaking skills of Dürr’s colleague Albert Oeri, the two were quickly engaged and married. Dürr was a widower with two small sons on whom Adrienne lovingly lavished her maternal care. The newlyweds moved to Basle’s Cathedral Square, where they had a fine apartment overlooking the Rhine.

- Adrienne von Speyr as a young woman

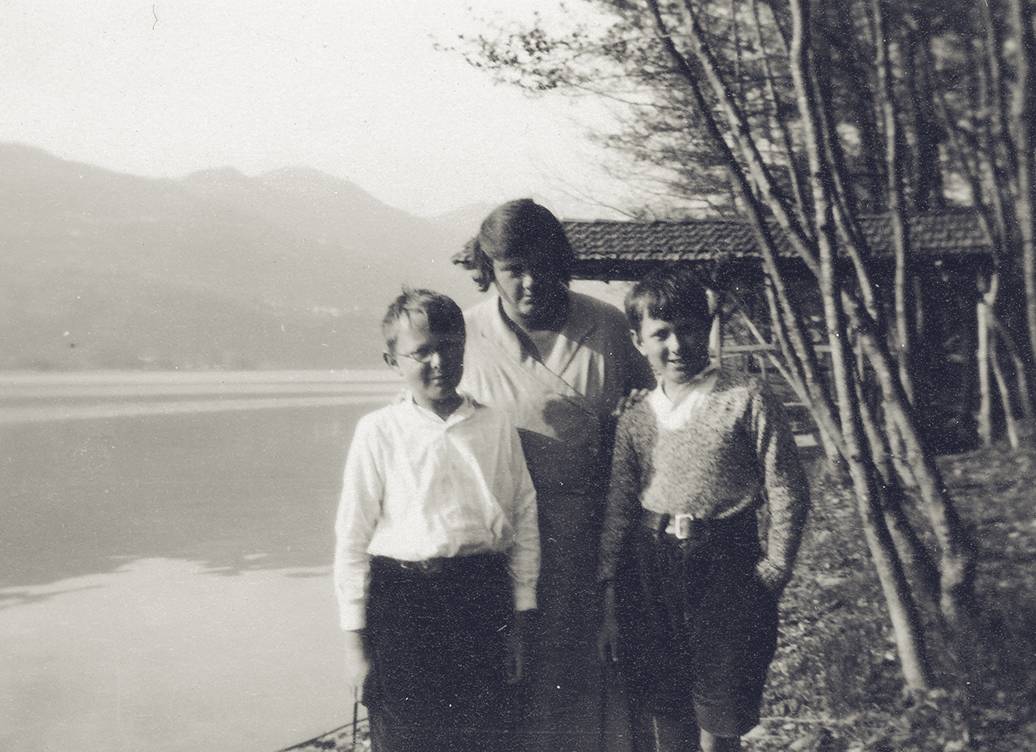

- Adrienne with Arnold and Niklaus, the sons of her first husband, Emil Dürr (ca. 1930)

At the time, Adrienne was still a student; it was only after a year of marriage that she was able to take her qualifying exam. Her first job was as a locum in the neighboring countryside, but she soon started a practice of her own. It was not long before she was flooded with patients, sometimes 60-80 a day. Among them were many poor people whom she treated gratis. Always attentive to the whole person and his or her problems, the young Dr. von Speyr was instrumental in saving marriages, preventing abortions–around a thousand, Adrienne once said–and in resolving religious questions. She left a large number of sketches about the ethos of the medical profession, especially the human relationship between doctor and patient, which was eventually published under the title Arzt und Patient [Doctor and Patient].

Adrienne’s premonitions of her husband’s imminent death proved to be true: Emil Dürr died as the result of a fall from a streetcar. Two years later–in 1936–Adrienne married Professor Werner Kaegi, a historian at the University of Basle who had written the life of Jacob Burckhardt.

Conversion and Mission

On November 1st, 1940, Adrienne’s long struggle to find true Christianity finally came to an end with her conversion to the Catholic Church. This bold step initiated a new period of her life marked by an abundance of graces that can only be described as charismatic.

Her prayer increasingly centered on the contemplation of Holy Scripture, and it was her prayer, rather than any theological preparation, that enabled her to author a number of scriptural commentaries. Her preferred method of writing was to dictate–in a simple, natural manner without any exaggerated piety or false enthusiasm–for about a half hour every afternoon. Adrienne’s works on Scripture, together with her other theological and spiritual writings, total about 70 volumes.

Adrienne’s literary activity remained a kind of sideline to her domestic, professional, and social life. Far from being self-involved, she was always on the lookout for ways to do nice things for others. She was a tireless and extremely generous gift-giver who gave in a characteristically cheerful, humorous, and child-like way–preferably anonymously. But she herself had a rare gift for receiving gifts, too; she did it with gusto and without false modesty. The atmosphere of uncalculating love, of “gratuity,” was her proper element. The same was true of her activity as foundress of a religious community for women, which she presided over with great dedication and a remarkable combination of maternal kindness and sober prudence.

Adrienne in Basel with a group of women from the Community of Saint John (1950’s)

Adrienne’s Final Years

Even before her conversion, Adrienne had experienced serious heart problems, which were soon aggravated by severe diabetes. Her nights were almost entirely given over to suffering and prayer. Soon after her conversion, she was obliged to keep to her bed until around noon every day; she typically was unable to sleep until the early hours of the morning. (Nevertheless, the dictation of her writings and her work as co-foundress continued apace until at least 1949.) Thanks to her habitual self-control, she generally managed to conceal her problems, heart and otherwise, from those around her. Nevertheless, she was eventually forced to see fewer patients and, as time went on, to give up her practice altogether. Thus began the long years of retirement in which she would spend her afternoons in silent prayer knitting intricate quilts. Once she began to lose her eyesight, she eventually had to stop knitting as well. Now almost totally blind, she sought to wrest a few letters from her long afternoons.

Adrienne displayed intensely persistent energy in her struggle with illness and suffering. She forced herself to descend the steep staircase to her work-room, even though she needed help to make the return journey upstairs. Physically speaking, her final months were one long torture, but she bore it in a spirit of perfect calm and serenity. During the final days of her life, she spoke of her happiness at the prospect of death: “How beautiful it is to die,” since, as she explained, she had nothing to look forward to but God alone. She breathed her last on September, 17th, 1967 and was buried [at Hörnli cemetery →] just a few days later, on what would have been her sixty-fifth birthday.

Providence itself, so it seems, sought to veil the powerful, clear light emanating from Adrienne von Speyr’s personality: All her activity and suffering took place in a curious concealment, as if God had immediately taken it out of her hands and claimed it for himself alone. God’s sovereign decree alone will decide whether the veil is drawn back from before this extraordinary ecclesial soul.

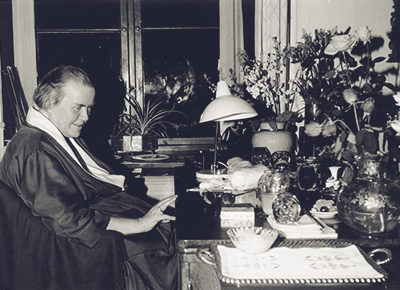

- Adrienne von Speyr at her desk (1965)

- Adrienne’s tomb in Basel (show on map). The sculpture (the inspiration for our site logo) is an evocation of the Trinity by Albert Schilling

- Adrienne von Speyr at her desk (1965)

- Adrienne’s tomb in Basel (show on map). The sculpture (the inspiration for our site logo) is an evocation of the Trinity by Albert Schilling

Further Reading

- Balthasar, Hans Urs von, First Glance at Adrienne von Speyr. 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2017).

- “Adrienne von Speyr. Participation in Christ’s Passion and Abandonment”, available on this website.

- “Adrienne von Speyr. Life and Legacy Podcasts,” at https://www.discerninghearts.com/catholic-podcasts/adrienne-von-speyr-podcasts/